3,500 years with a disease that affects (along with its precursor) more than one-third of Americans

CAROL ANN WILSON | November 14, 2018

If you don’t have “diabetes,” someone close to you does. That’s “diabetes” in quotation marks because that’s what we call it, but the disease is part of a much bigger problem: metabolic failure.

If you don’t have “diabetes,” someone close to you does. That’s “diabetes” in quotation marks because that’s what we call it, but the disease is part of a much bigger problem: metabolic failure.

As of 2015 (the most recent year for data), 30.3 million Americans had diabetes—9.4 percent of the U.S. population—according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Another 84.1 million were prediabetic, meaning that untreated they would likely have diabetes within five years. According to the American Diabetes Association, the total economic cost of diabetes in the U.S. increased from $205 billion in 2007 to $327 billion in 2017.

Those numbers have steadily increased. They have never declined. The most that physicians even hope for is that their diabetic patients maintain their status or that they don’t get too much worse.

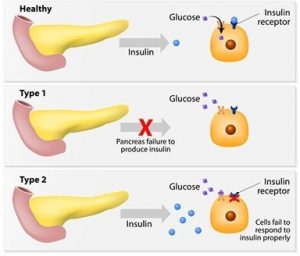

There are two main forms of diabetes: Type 1, formerly called juvenile diabetes because it is a kind of birth defect wherein the person’s pancreas produces no insulin or the person does not even have a pancreas, and Type 2, formerly called adult-onset diabetes because it develops later in life.

I have spent hundreds of hours researching diabetes—because I was diagnosed a diabetic at 68—and want to share a few things I have learned about the history of this awful disease, in layman’s terms. Most diabetics and those who love them should find something of interest here.

The Ancients

Around 600 BCE, a Hindu physician in India named Sushruta, a legendary scholar of Indian medicine, wrote textbooks in Sanskrit that stand today among the most important ancient medical treatises. His work was later translated to Arabic, Latin, English—well, most languages, now—and serves as the foundational text of medical tradition in India. Sushruta is often referred to as the founding father of surgery.

He described diabetes as a disease characterized by the passage of large amounts of urine, sweet in taste. Sushruta said the disease affects primarily obese people who are sedentary, and he emphasized the role physical activity could play in lessening its effects.

He tested for the disease by observing whether ants were attracted to a person’s urine, and he also called it “sweet urine disease.” Two types of diabetes were identified as separate conditions for the first time by Sushruta, with the first type associated with youth and the second with being overweight. Prescient!

In 250 BCE, Apollonius of Memphis (today Cairo) is credited with coining the term diabetes from the Greek term meaning “to go through or siphon,” for a disease that drains patients of more fluid than they can consume.

In the second century, Aretaeus the Cappadocian, a Greek physician who revived Hippocrates’ teachings and practiced in Rome and Alexandria, named the condition diabeinein for causing the patient to pass too much water. After his death he was entirely forgotten until two of his manuscripts were discovered sometime around 1550. More than any other physician of antiquity, his name has been linked with diabetes. Blessed with a gift for words, he produced the first clear written description of the disease. In the January-March 2012 edition of Hormones, his description is called “outstandingly vivid and accurate.”

Note his description, from some 2,000 years ago:

Diabetes is a remarkable affliction, not very frequent among men. […] The course is the common one, namely, the kidneys and the bladder; for the patients never stop making water, but the flow is incessant, as if from the opening of aqueducts. […] The nature of the disease, then, is chronic, and it takes a long period to form; but the patient is short-lived, if the constitution of the disease be completely established; for the melting is rapid, the death speedy. Moreover, life is disgusting and painful; thirst, unquenchable; excessive drinking, which, however, is disproportionate to the large quantity of urine, for more urine is passed; and one cannot stop them either from drinking or making water. Or if for a time they abstain from drinking, their mouth becomes parched and their body dry; the viscera seems as if scorched up; they are affected with nausea, restlessness, and a burning thirst; and at no distant term they expire. They thirst, as if scorched up with fire. […] Hence, the disease appears to me to have got the name diabetes as if from the Greek word [signifying a siphon], because the fluid does not remain in the body, but uses the man’s body as a ladder, whereby to leave it. They survive not for long, for they pass urine with pain, and the emaciation is dreadful; nor does any great portion of the drink get into the system, and many parts of the flesh pass out along with the urine.

— The extant works of Aretaeus, the Cappadocian

by Francis Adams

The Sydenham Society, London

Toward the Modern Era

Going through history, we assume that medical practitioners followed the work of these ancient heroes, but we still do not see much progress in treating the disease or even in making diagnoses. Because the urine of people with diabetes was “sweet tasting,” for several centuries the condition was often diagnosed by water tasters—people who drank the urine of those suspected of having diabetes.

Paracelsus, the father of toxicology Paracelsus, credited as the father of modern toxicology, identified diabetes as a serious systemic disease. Wikipedia Commons

Then in the 1500s we find Paracelsus, a Renaissance-era Swiss contemporary of Copernicus, Leonardo da Vinci, and Martin Luther. Paracelsus was a colorful character. Credited as the father of toxicology, he believed strongly in the diagnostic properties of urine, and he identified diabetes as a serious systemic disease. Paracelsus was a medical revolutionary who established the role of chemistry in medicine. Carl Jung called him “not only a pioneer in the domains of chemical medicine, but also in those of an empirical psychological healing science.” A famous Paracelsus quote urges keeping wounds clean: “If you prevent infection, Nature will heal the wound all by herself”—still excellent advice today.

In the next century, around 1675, Thomas Willis, personal physician to England’s King Charles II, coined the term diabetes mellitus, adding a Latin term meaning “sweetened by honey.”

Another century passed, and in the very-important-to-us year of 1776, Matthew Dobson, a Liverpool physician, contributed to the fifth edition of Medical Observations and Inquiries (for a society of London physicians) confirmation that the urine of diabetes patients was sweet to taste and after evaporation contained a large amount of white, granular material that was indistinguishable from sugar. Dobson also observed that the blood serum was sweet to taste, and thus he is called the discoverer of hyperglycemia.

Dobson observed that, for some people, diabetes is fatal in less than five weeks and for others it is a chronic condition. Apart from Sushruta’s important work, this appears to be the earliest distinction between Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes. Dobson deduced that diabetic urine always contains sugar that is not formed in the kidney but previously existed in the serum of the blood. This simple observation, that diabetes is associated with a persistently raised blood sugar concentration, pivoted diabetes research in the right direction, toward the mechanisms by which the body deals with carbohydrates. For this, he deserves mention in our layman’s history of diabetes.

In 1797, John Rollo, a surgeon in the British Royal Artillery, applied the first significant dietary approach to the treatment of diabetes in his book An Account of Two Cases of the Diabetes Mellitus. He successfully treated a patient using a high-fat and high-protein diet after observing that sugar in the urine increased after eating starchy food.

Diabetes Mellitus Diabetes mellitus, the latin term meaning “sweetened by honey”, was coined by Thomas Willis around 1675. Shutterstock

Rollo studied one Captain Meredith, 232 pounds, who suffered from intense polyuria and dehydration. Captain Meredith’s diet was adjusted to one rich in protein and animal fat and low in carbohydrates, in addition to medications. The result was substantial weight loss, the elimination of Meredith’s symptoms, and the reversal of both his glycosuria and hyperglycemia. Rollo’s study was a seminal point in unraveling ages-old mysteries about diabetes.

Things get busier around 1857, when French physiologist Claude Bernard reports his discovery that glycogen is formed by the liver and speculates that this is the same sugar found in the urine of diabetics. His discovery resulted from his work on the pancreas and was the first linking of diabetes and glycogen metabolism.

In 1869, Paul Langerhans Jr., a German medical student, wrote in his thesis, “Contributions to the Microscopic Anatomy of the Pancreas,” of his discovery of nine different cells in the pancreas (which he dubbed the abdominal salivary gland) and his conclusion that the beta cells help produce a hormone that would later be identified as insulin. Years later, these cells are called the islets of Langerhans. Since 1978, the German Diabetes Association has awarded the Paul Langerhans Medal to great achievements in diabetes research.

In 1889 in Alsace, France, Oskar Minkowski and Joseph von Mering surgically removed a dog’s pancreas, inducing in the animal severe and eventually fatal diabetes.

Since 1966, the European Association for the Study of Diabetes has awarded the Minkowski Prize for outstanding contributions to the advancement of knowledge in the field of diabetes mellitus.

Toward Treatment

German physician Georg Ludwig Züelzer helped advance the treatment of diabetes when in 1903 he began experimenting with the pancreatic extracts of animals to inject into the bodies of other hyperglycemia-induced animals. In 1908, he used the extractions of calf pancreases to make a substance (“Acromatrol”) that he would inject into five diabetes patients. Although the patients showed initial improvement, they died from the treatment’s side effects. While Züelzer was not successful, his work helped lead to the identification of insulin.

Then in 1909, Belgian clinician and physiologist Jean de Meyer proposed the name insulin (Latin for “insula” or “island”) for the internal secretion of the pancreas, but the substance would not be isolated for several more years.

In 1913, Harvard’s Frederick Madison Allen published the book Studies Concerning  Glycosuria and Diabetes, stimulating a revolution in diabetes therapy. He and another physician, Elliott P. Joslin, became the foremost American experts on the disease. Joslin wrote The Treatment of Diabetes Mellitus, the first English medical textbook on the disease, and Diabetic Manual—for the Doctor and Patient, aimed at helping patients cope with diabetes —both classics. Joslin believed diabetes to be “the best of the chronic diseases” because it was “clean, seldom unsightly, not contagious, often painless, and susceptible to treatment.” (We diabetics question the “painless” part.) Today the Joslin Diabetes Center in Boston is the world’s largest diabetes research center and clinic.

Glycosuria and Diabetes, stimulating a revolution in diabetes therapy. He and another physician, Elliott P. Joslin, became the foremost American experts on the disease. Joslin wrote The Treatment of Diabetes Mellitus, the first English medical textbook on the disease, and Diabetic Manual—for the Doctor and Patient, aimed at helping patients cope with diabetes —both classics. Joslin believed diabetes to be “the best of the chronic diseases” because it was “clean, seldom unsightly, not contagious, often painless, and susceptible to treatment.” (We diabetics question the “painless” part.) Today the Joslin Diabetes Center in Boston is the world’s largest diabetes research center and clinic.

Around the same time that Joslin and Allen published their first discourses on diabetes treatments, the revelation of additional insights were delayed by global events. Between 1914 and 1916 a distinguished Romanian scientist and physiologist, Nicolae Paulescu, developed a pancreatic extract which, when injected into a diabetic dog, had a normalizing effect on the dog’s blood sugar levels. Paulescu’s work was interrupted by World War I, and it was 1922 before he published an article describing his successful isolation of “pancreine” or insulin. His treatise, “Research on the Role of the Pancreas in Food Assimilation,” reports his 1916 discovery of the substance that normalized the blood sugar of a dog with diabetes. When Frederick Banting and John James Richard Macleod were awarded the Nobel Prize in 1923 for the discovery of insulin, Paulescu objected, claiming the discovery for himself. His claims were rejected, but eventually Paulescu was recognized for his significance in the history of insulin.

Meanwhile, Allen worked on treatments for diabetics, promoting a strict dietary regimen that was soon widely adopted. Allen limited his patients’ food quantities, believing the diabetic’s body could not utilize food. His patients were admitted to the hospital and given only whiskey mixed with black coffee (or clear soup for teetotalers) every two hours from 7 a.m. to 7 p.m. The patients continued his “starvation diet” until there was no sign of sugar in the urine — usually about five days. Unfortunately, the Type 1 patients commonly died during the treatment (probably from starvation!). Outcomes were better for Type 2 diabetics, and the young people who survived became the first insulin users

In 1919, Allen and two other physicians published Total Dietary Regulation in the Treatment of Diabetes, with exhaustive case records and observations of most of his 100 diabetes patients. He went on to become the Director of Diabetes Research at the Rockefeller Institute.

A year later, Canadian physician Frederick Banting is believed to have conceived the idea of insulin after reading Moses Barron’s “The Relation of the Islets of Langerhans to Diabetes with Special Reference to Cases of Pancreatic Lithiasis” in the journal Surgery, Gynecology and Obstetrics. With help of his student Charles Best, Canadian chemist James Collip, and Scottish physiologist John Macleod, Banting continued experimenting with various pancreatic extracts on dogs whose pancreases had been removed.

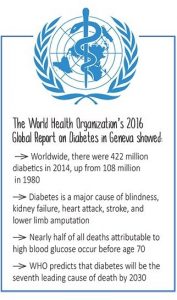

World Health Organization 2016 Global Report

Insulin was “discovered” in 1921 when a de- pancreatized dog was successfully treated with it. In Toronto in 1922, one of Collip’s insulin extracts was tested on a 14-year-old boy named Leonard Thompson who had Type 1 diabetes. The boy had been close to death before treatment, but he bounced back to life with the insulin. The news of this first medical success using insulin for treatment of a human with diabetes rapidly spread, and Eli Lilly and the University of Toronto began mass producing insulin in North America. Leonard Thompson lived another 13 years, dying of pneumonia at 27.

Another early diabetes treatment story had a happier ending. On Aug. 16, 1922, Elizabeth Evans Hughes, the 13-year-old diabetic daughter of U.S. Secretary of State Charles Evans Hughes, arrived in Toronto to be treated by Dr. Banting. She weighed only 45 pounds and was barely able to walk but responded immediately to the insulin treatment. Elizabeth went on to live a productive life and in 1981 died of natural causes at age 73. Her life is chronicled in a 2010 book by Thea Cooper and Arthur Ainsberg, Breakthrough: Elizabeth Hughes, the Discovery of Insulin, and the Making of a Medical Miracle.

While insulin was shown to prevent early death from diabetic coma, insulin treatment did not, and to this day does not, prevent the chronic, disabling, and sometimes deadly complications of the disease, such as neuropathy (nerve damage), nephropathy (kidney damage), poor wound healing, and retinopathy (retina damage). There is no substance nor has any drug yet been developed that treats the root cause of diabetes, which is metabolic failure.

In his Nobel Prize lecture Banting said, “Insulin is not a cure for diabetes; it is a treatment. It enables the diabetic to burn sufficient carbohydrates, so that proteins and fats may be added to the diet in sufficient quantities to provide energy for the economic burdens of life.”.

In 1940, the American Diabetes Association was founded to address the increasing incidence of diabetes and its complications. Today the Association comprises a network of more than 1 million volunteers; a membership of 500,000 people with diabetes, their families, and caregivers; a professional society of some 14,000 health care professionals; and a staff of 800.

In 2017, it reported revenue of $162 million. The Association’s founding and growth coincided with a growing awareness—and incidence—of the disease.

In 1948, Joslin wrote about the “unknown diabetic” in Postgraduate Medicine. Although by that time 1 million people were known to have diabetes, Joslin speculated that a million more had it but did not know they did. He is the first prominent expert to emphasize that insulin alone cannot solve all diabetes-related issues.

Products Developed for Diabetics

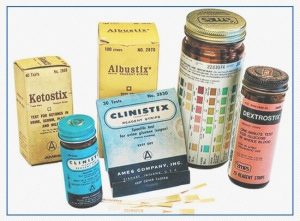

In the late 1940s, American chemist Helen Murray Free developed the “dip-and-read” urine test (Clinistix) and other tablet-based tests for instant monitoring of blood glucose levels, in her work at Miles Laboratories (now owned by Bayer AG). While retired from full-time work, Free still serves as an adjunct professor of management at Indiana University, South Bend, and a Bayer AG consultant. President Obama awarded her the National Medal of Technology and Innovation in 2009.

The mid 1950s saw the introduction of oral drugs that helped lower blood glucose levels, including sulfonylureas, oral medications that stimulate the pancreas to release more insulin. In the 1960s, home testing strips for glucose levels in the urine increased the level of personal control for people treating their diabetes. Ames (a division of Miles Labs) introduced the first blood glucose meter in 1970, for use in doctors’ offices. Developed by Anton H. Clemens, it weighed about 3 pounds and cost $650 (about $4,200 in today’s dollars). Insulin pumps and laser therapy, used to help slow or prevent diabetic blindness, were also rolled out in the 1970s.

1963: The first wearable insulin pump, which delivers both insulin and glucagon, is developed. At this point, the pump is still a prototype—it’s the size of a large backpack. American Diabetes Association

In 1973, U-100 insulin—which means there are 100 units of insulin per milliliter of fluid in a vial—was introduced, helping correct dosing errors. And in 1976 the HbA1c test, measuring average blood sugar over two to three months, came out and has become the standard for screening for diabetes and measuring longterm control. It’s generally the first thing doctors today want to know when treating patients with diabetic or prediabetic conditions: “What’s your A1c?”

In 1978, the federal government created the National Diabetes Information Clearinghouse to gather and document all diabetes literature and disseminate it via the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, a part of the National Institutes of Health, which is part of the Department of Health and Human Services.

Another turning point occurred in 1978 when the testing of the first recombinant DNA insulin was announced. Until then, insulin manufacturers had to stockpile animal pancreatic tissue. With this development, recombinant DNA technology (genetic recombination, such as molecular cloning) allowed the manufacture of a genetically engineered “human” type of insulin, and 1983 brought the first biosynthetic human insulin.

Reflolux, later known as AccuChek, was introduced in 1983. It allowed relatively easy and accurate blood glucose self-monitoring and was followed in 1986 by the insulin pen delivery system. In 1995, the drug metformin became available in the U.S. Metformin is a biguanide that prevents glucose production in the liver. The drug remains in wide use today. And in 1996, the Food and Drug Administration approved the first recombinant DNA human insulin analogue, lispro (Humalog).

1964: The Ames Company introduces Dextrostix, the first test strips that use a drop of blood to measure glucose levels, providing real-time information about blood glucose levels for diabetics and prediabetics. American Diabetes Association

Root Cause and My Story

Without exception, all the organizations and associations aimed at curbing diabetes or helping people live with it advocate lifestyle changes and prevention as the only way to reduce the burden caused by the disease. They urge early diagnosis, along with changes in diet and exercise.

It sounds like these experts think that we have done this to ourselves. But are we the ones who have for decades crammed high-fructose corn syrup and other sweeteners into just about every product on grocers’ shelves. Are we the ones who have caused the medical community to treat symptoms instead of the diabetes root cause? Did we cause the marketing frenzy of pharmaceutical ads or the large business of treating the disease?

I don’t think so, and I think that no medical school provides proper education on natural substances for keeping us healthy. Thankfully, an increasing number of physicians are now helping us educate ourselves and take control of our health.

I can personally advocate for one company with a physiologic insulin delivery treatment that concentrates on the root cause, which is metabolic failure. We learned that the pancreas and liver must be retrained to communicate with each other just as God’s design intended. Diabetes Relief, which patented treatment for improvement in impaired hepatic glucose processing, took a long-known idea and refined it for lasting results. As a co-inventor of the patent granted in May 2017, my heart expands as I see hope restored for other diabetics suffering from the many complications of this awful disease. My journey through the history of diabetes changed my life and is now helping others to change theirs.

Nov. 14 is World Diabetes Day.

_______________________________________________________

Carol Ann Wilson

Carol is a self-employed writer and researcher who lives in Houston. Her background is legal, and she holds several certifications. She currently serves as executive secretary for Diabetes Relief LLC, where she is responsible for written communications and assists legal counsel. She is the author of Plain Language Pleadings, has co-authored other works, has 25 years as a newsletter editor, and is a longtime member of Plain Language Association International. Visit her website (carolannwilson.net) or send her an email (carolwilson@earthlink.net). Gulf Coast Mensa | Joined 2000

REPRINTED WITH PERMISSION FROM Mensa Bulletin, November/December 2018; www.us.mensa.org/read/bulletin/features/sweet-talk-a-laymans-history-of-diabetes